The short version

If you are an aging, slightly art-damaged music nerd with a penchant for the 90’s and vinyl, you need to buy this book. If you have ever self-released music, or helped assemble a run of hand-made packaging: you need to buy this book. If the words “Fest band” conjure up vivid imagery for you, you especially need to buy this book.

If you know someone who meets any of these descriptions, and you are looking for a Christmas gift for them: you need to buy this book for them. This is the book my brain has been silently willing someone to compile for years.

Ok, now the long version

Earlier this year, I wrote an article discussing the various capabilities unique to the vinyl record as a format. It ran in the July / August issue of The Believer, and while it focused on the oddities that can be pressed into the physical record itself, I’m pretty sure I managed to clumsily allude to the concept of the “record as an artifact” somewhere in there.

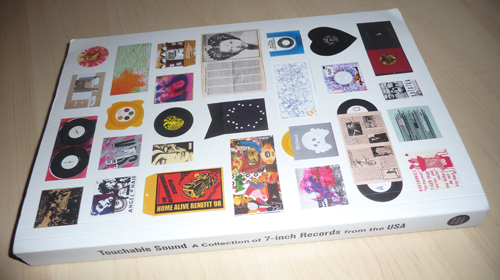

A few months back, at the end of a random chain of links I’d clicked through, I stumbled across a book called Touchable Sound – A Collection of 7-inch records from the USA, published by Soundscreen Design. An entire book focused on the concept of the 7″ record as a physical artifact?! And it was already available?!

I broke my current ‘Try not to acquire so damn many books’ embargo (It isn’t working anyway) and ordered it immediately, hoping for the best.

I should say here that like any book-oriented music nerd, I have been burned by my fair share of ‘Album art’ books in the past. There is no shortage of books on the subject, and the bulk of them treat the artwork as a flat, square visual experience – completely divorced from the physical object onto which it is printed. Furthermore, the covers included in such collections often seem to have been selected based on the names of the artists on the records they were created to package (Try to find an album art retrospective with no Beatles, Rolling Stones, or Pink Floyd). I couldn’t be happier to report that this book is the exact opposite of those books – the content was seemingly selected with absolutely no attention payed to the audio component of the artifact at all. All records that are included are painstaking, tactile creations, photographed as objects.

Obviously, a big part of why this book connected so strongly with me is because the years during which I was personally immersed in record nerdery fall within the window of time it covers – Troubleman Unlimited owner Mike Simonetti perfectly summarrizes a few of my formative teenage years in one brief sentence:

“The process involved scouring zines for advertisements or reviews, sending “well-concealed cash” to the label (whose owner hopefully hadn’t moved in the time it took the ad to reach the reader), and checking the mail every day for up to a year while waiting for the record to arrive-if it actually showed up at all.”

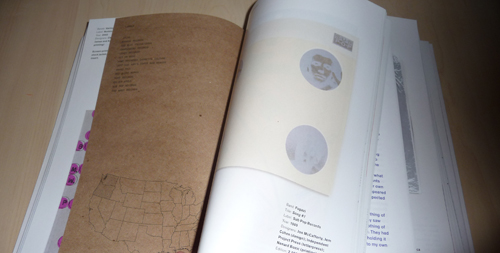

I think there’s a lot more to the book than simple nostalgia or designy navel-gazing, though. Beyond getting the selection process right, the editors have added several additional layers of context to the records they present: the collection is broken down by region, and by label within each region. These regional sections are punctuated with essays written from the unique perspective of the label owners that facilitated many of the records pictured elsewhere in the book.

Much of the sneaky dual-function I see in this book lies in these essays. Themes that don’t often appear in ‘Business of music’ books are covered from a number of viewpoints, and the wheathered tone of experience runs through all of them. Discussed: the economic necessity that often informs aesthetics or design choices, the romanticism and ritual of production-line record assembly (The first section of Chunklet Editor Henry Owings’ introduction is titled “I’ve spent months of my life assembling records. No Joke.”), and the weird mix of futility and passion inherent in pouring hours of manual labor into a musical artifact aimed at a limited audience (A refrain of “What were we thinking?” echoes throughout the book).

(An aside: if you are currently involved in producing vinyl in any way, it is worth paging through this book solely to marvel at the ridiculous press runs some of these 90’s records had.)

Perhaps the most striking section of the book is the afterward – an interview with Sam McPheeters, one-time singer in Born Against and helmsman of Vermiform records. Though making and selling music were both central elements of his life at one time, he now spends the bulk of his time as a writer. This distance has seemingly put some of the DIY revolution he lived through into perspective, and he isn’t shy about cutting through the romanticism:

“Throughout the 1990’s, the disincentives to identify with underground music (violence, ridicule) plummetted at the same rate that the cost of production (CD pressing, online distribution) plummetted. But the subculture’s core message – anyone can do this! – remained constant. So bands and fanzines and record labels became the default pursuits of a generation. A lot of people think this is a good thing. I don’t. I know too many folks who plod along with their bands or record labels purely due to inertia, because underground creativity is a tradition that extends just far enough past their own life span that it seems like an enduring lifestyle. That was certainly my sorry state for a few years.”

“I understand this is an elitest sentiment, but consider the big picture. The specific era covered in your book-megawealthy post-Cold War America-is an anomoly in human history. Not everyone should make art. Not everyone should be in a band. Some people have to farm, and repair bridges, and make socks. I certainly wish I’d learned some practical trade 20 years ago.”

Whether you agree with his sentiments or not, the five-page interview serves as a perfect coda to the conflicted narrative built up by the arrangement of the book: full-color sections celebrating these artifacts, sandwiched between the often melancholy conversations with the people responsible for creating them.

Inception

So: I cannot stress how much I loved this book, and how much I would love for further volumes to someday be assembled. But! Sometimes, reading about the production of nerdy things (in this case, records) just isn’t quite enough – sometimes I want to read about the production of nerdy things (books) that are themselves about the production of nerdy things (records). Luckily, Mike Treff, one of the editors of the book, was kind enough to answer some questions I had about how the book was put together. Book nerd alert.

Me: What’s the story behind the book? Did all of the editors have a background in running labels?

“When I started Soundscreen, the idea for this book was something I had been kicking around for a long time. I was already working with Brian Roettinger (my co-editor and the book’s designer) on our company’s identity, and his background running Hand Held Heart, both a record label and design shop, was perfect for this project. We talked about this book and just dove right in. Diego Hadis (co-editor) and I were working together on a few projects, and he had previously worked at what was my favorite NY record store, Sound and Fury, for years.”

“I have always been fascinated with the 7-inch as a format, and further by the amount of labor that went into so many of the records I bought growing up at hardcore shows. Often a record clearly took months to make, with the band or label screen printing, embossing, die-cutting, and using just about every other mode of production known to hand to make a record, that they ended up selling for $3. While that effort alone is enough to fill the 412 pages of Touchable Sound, we also wanted to highlight the exceptional design and packaging that was resulting from this approach. It’s a vital part of the story of underground music that is rarely told. Just like poster books, there are many books on record design that focus singularly on the cover image, which in the case of Touchable Sound is only a fraction of the story. It’s that story we wanted to capture.”

Me: How did the work break down amongst the various contributors?

“It was a total team effort, all the way around. We all were involved in the selection process, we all did research, we all collected information for the records. When it got tactical, we each played to our strengths. Brian took the lead on design, and Diego took the lead on actual text editing. As editor and publisher, I handled much of everything else, from production to content creation to sales and marketing.”

“It was a near 2 year process from start to finish, which given the fact we reviewed almost 30,000 records, doesn’t seem that bad!”

Me: What was the selection process like? Were there any tough decisions as far as what to include and what not to include?

“The selection process was endless, literally. We would be prepared to review the next 500 records for consideration, we’d discover a new label or band or collection to mine that we had not previously included, and so it began again. We probably had at least 20 review sessions where we went record by record to determine the final set, and that’s after we each reviewed countless records to bring our recommendations to the selection reviews.”

“There were a ton of heated discussions about why a particular record needed to be included or discarded, but that was actually a really fun part of the process. We each had our own sensibilities and ideas for what the final set should include, and I think we found a nice balance in the end. I do feel like its a well rounded collection, that is representative of all the different aspects of our general theme, exceptionally packaged, labor-intensive 7-inch records.”

Me: Do you have a personal favorite among the records featured?

“YES! SO MANY, too many to list. While there are certainly bodies of work that stand out to me as exceptional, such as all the Melvins records and the Gravity Records included, but there are just so many singular records that are among my favorites, and for a variety of reasons, that I couldn’t really single one out.”

Me: The presentation of the book itself echoes the appreciation for unique tactile experiences that seems to have inspired the book in the first place. Were there any crazy hoops you had to jump through to get a book with several sections of half-pages bound?

“For sure, but we wanted the book to be representative of the content contained within. The book had to be just as much an impressive object as the records showcased are. We did jump through many hoops to finally get the design we wanted, including many many budget revisions, but fortunately we had a great partner in Shapco, who handled the books production. We’re very thankful for their effort in helping to make this book as we dreamed it.”

Deleted Scenes

The last question I asked was for an example of a record that barely missed inclusion in the book – a “deleted scene” of sorts. Mike conferred with his fellow editors, and came back with a whole list of near-misses. I’ve assembled them below. These are records that didn’t make the final cut for inclusion – so that should speak to the quality of the collection while simultaneously serving as a teaser for what else is out there.

Mike: “Ok, here goes, these are records that ALMOST made it…lots of deals made very late at night surrounding these records…”

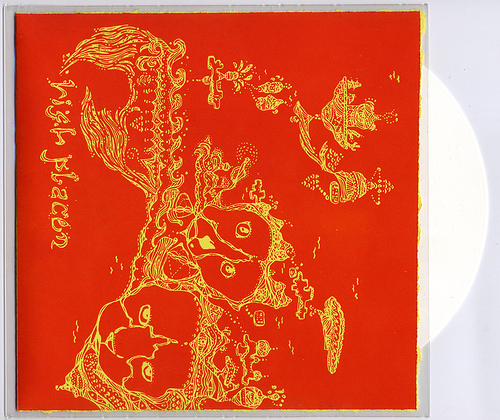

High Places – s/t (Ancient Almanac, 2007)

All sleeve artwork was hand plated and pressed by Rob & Mary of High Places.

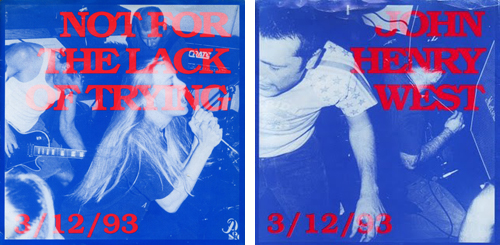

V/A – 3/12/93 (Ebullition, 1993)

“On 3/12/93, Sinker, John Henry West, Manumission and Not For The Lack of Trying played a show at the Anaconda in Goleta, CA. The idea was that all four bands would play a show together and then release a 7″ comp based on that show. Everyone that attended the show wrote their name and address down in a notebook and when the record came out they recieved a copy with a hand screened cover. The cover can be folded to display any of four covers. All of the photos were taken at the show on 3/12/93.” [link]

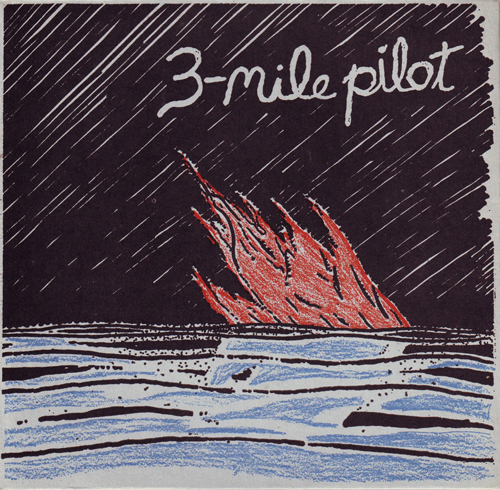

Three Mile Pilot – Piano Minus, Piano Plus (Pennyfarthing Records, 1996)

[I couldn’t find any information about the packaging to this one. Help me, internet…]

Poison 13 – Ain’t Superstitious (Estrus, 1995)

Double 7″ pressed on clear and red vinyl. Includes gatefold jacket with pop-up glow-in-the-dark skeleton, paper OBI band.

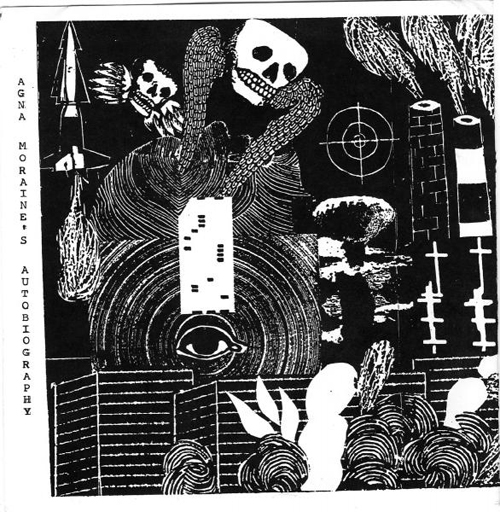

Agna Moraine’s Autobiography – s/t (Anima, 199?)

Hand-made packaging with lyrics silkscreened on four seperate colored cloth patches.

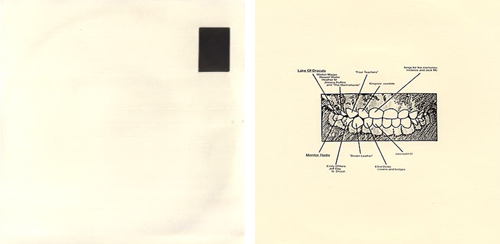

Lake of Dracula / Monitor Radio – split (The Carcrash Label, 1998)

White Vinyl & die-cut sleeve with an actual dental x-ray individually glued in.

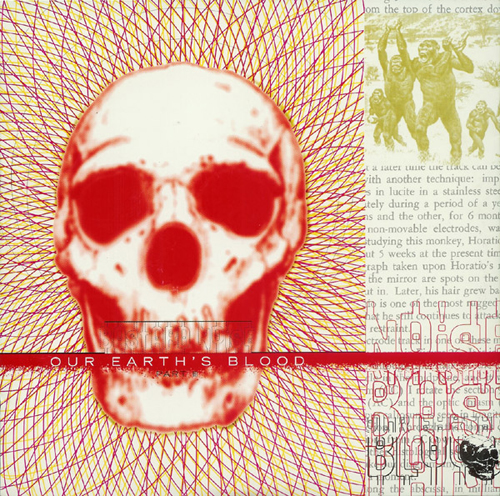

Bastard Noise – Our Earth’s Blood Part III (Rhetoric, 1996)

[Another one for which I couldn’t find any specifics about the packaging.]

Commenter “Housepig” adds: “This was designed by WT Nelson of Thumbprint Press / Unicorn / Bastard Noise, including the design of the custom font on the lower right cover and insert.”

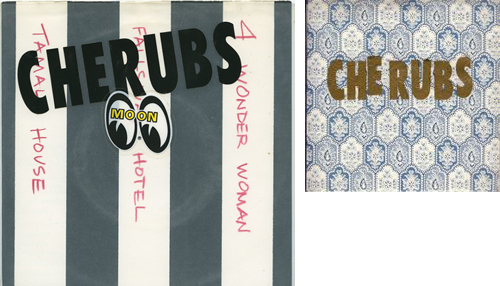

Cherubs – Carjack Fairy (Trance Syndicate, 1993)

Each with unique, hand-cut wallpaper sleeves and vinyl lettering.

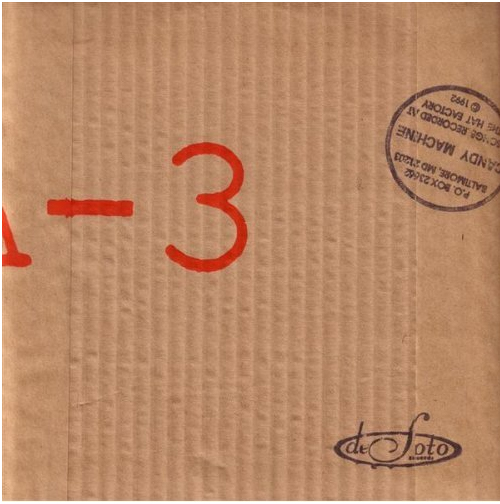

Candy Machine – “History of a Bourgeois Revolution” (Desoto, 1992)

Record was issued in a hand-stamped and screened corrugated cardboard sleeve. “Hard to describe, but the sleeve had to be destroyed to open.”

Wingtip Sloat – s/t (Sweet Portable Junket, 1991)

Numbered edition of 500 copies, each copy has two entirely different cover slats and many (dozens) of inserts and pieces of ephemera.

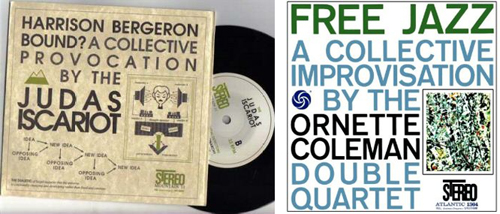

Judas Iscariot – Harrison Bergeron Bound (Mountain, 1997)

[Design apes Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz design, but I couldn’t find any specifics on the production of the packaging.]

The Go Team – Series (K records, 1989)

Series of monthly releases in 1989. Each record comes bagged in a clear plastic sleeve, with two songs on one side and a custom-silkscreened design on the other. In true Go Team spirit, no two in a row sport the same personnel: Tobi and Calvin play on all of them, and their musician friends stop by to sing or play. [link]

Moving Pictures

Mike Treff and Henry Owings recently did a lecture of sorts to promote the book, and it’s available on Youtube in three parts. Highly recommended to get a flavor for what the book is all about:

Part One:

Part Two:

Part Three: