While going through a stack of old issues of the Chicago Reader for another project, I happened upon the April 14th, 1994 issue, which featured a few selected reactions to Kurt Cobain’s then-recent suicide.

The first words in the feature come from Steve Albini, and the no-nonsense type treatment that the Reader’s designers gave to his copy seemed to match his tone perfectly. I was surprised when I googled to find that this article seemingly hasn’t made it onto the internet.

So, here it is in full: “Nevermind the Bullshit: An Outsider’s Reminiscence:”

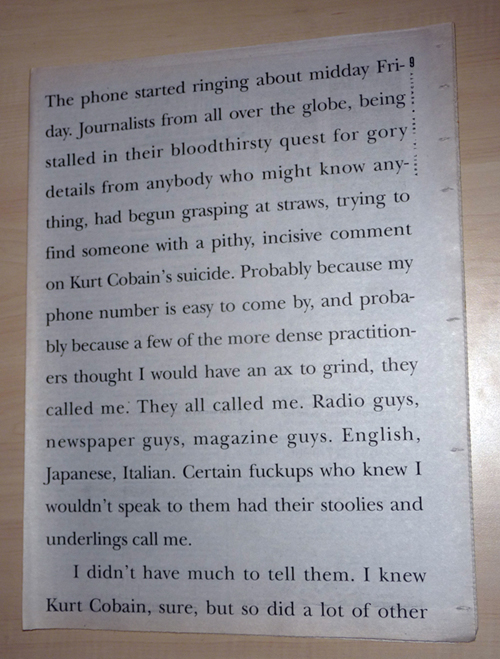

The phone started ringing about midday Friday. Journalists from all over the globe, being stalled in their bloodthirsty quest for gory details from anybody who might know anything, had begun grasping at straws, trying to find someone with a pithy, incisive comment on Kurt Cobain’s suicide. Probably because my phone number is easy to come by, and probably because a few of the more dense practitioners thought I would have an ax to grind, they called me. They all called me. Radio guys, newspaper guys, magazine guys. English, Japanese, Italian. Certain fuckups who knew I wouldn’t speak to them had their stoolies and underlings call me.

I didn’t have much to tell them. I knew Kurt Cobain, sure, but so did a lot of other people. I wouldn’t call him a friend, but not because I didn’t like him. I met him too late in the game for a real friendship to have been possible. By then, he was already a millionaire rock star. He was surrounded by people whose status and income depended on his popularity. All of those people and more presented themselves as his friends.

He was smart enough and realistic enough to know that someone popping out from behind a bush trying to be his friend probably had an angle. He was weary from those people being his friends. Out of respect for what remained of his patience, I never pressed him for any intimacy.

My impression of him is probably as skewed as anybody else’s. I saw him during a resolute period, where he and his band were operating at capacity: productive, confident and (mostly) at ease. There were obviously episodes before then and since where things were not going so well, but I’m disinclined to speculate why. Plenty of other people who knew him less than I did will do that for you.

I was and remain an outsider to the daily goings-on within the band and in Kurt’s life, like a small child dazzled and a little frightened by a carnival, which others around him took little notice of. As an outsider. I had benefit of a neutral perspective when weird things occurred, as they do in the lives of all important people.

I realized how different their world was from mine the first day I was in the band’s company. Krist Novoselic had brought a pile of settlement papers with him from Washington for the band to sign. The settlements were for different nuisance law-suits that had sprung up like fleabites once the band became successful. Sign here, and give a few grand to someone who claims a splinter from a broken bass guitar got in his arm, requiring traumatic tweezing. Sign here, and give a house down payment to some bastard who says somebody in Nirvana was once in a band that was once in debt to him for a phone bill. Sign here, and pay off somebody for remembering that his high-school band was once named “Nirvana.” Sign here, and put some greedy bastard’s kid through military school because he wore a Nirvana T-shirt to a wake, traumatizing the guests.

The nonchalance with which these parasites were bought off, as though it were a common and insignificant chore, dumb-founded me. The band, before breakfast, had dispersed more money to liars and cheats than I would make in a year or more.

There seemed to be no end of badgering crap. Everybody, everywhere wanted a piece of them; wanted them to pony up and pay the street tax on the road to popularity. In addition to the periodic bleedings they had to endure, there was the constant intrusion of the world at large into their lives. A journalist with a chip on her shoulder had almost cost Kurt his daughter, whom he loved with more enthusiasm than any other thing. The authorities, once tipped, belligerently ignored the plight of the thousands of truly unloved and uncared for children whose parents didn’t happen to be famous, in an attempt to make an example of a nontraditional couple.

Another pair of would-be journalists (crazed groupie chicks, actually) had been hounding Kurt, his wife, and all of their friends while “researching” a “book.” Their research apparently included seducing Family members, swiping personal artifacts, and accosting them in public, in an attempt to cause a “scene.”

Traveling in rock-music circles makes dealing with death inevitable. There is a persistent and pathetic association between extremes of lifestyle, indulgence, obsession and rock music. ln the last couple years, l’ve seen a half-dozen friends and acquaintances die or pretty much so. It’s a drag, and it’s a shame, but as long as there are suckers for the myth of the outlandish rocker, there will always be people to encourage them and profit from their decline. They’re also going to die once in a while. That’s part of the myth, too.

Every thinking person has, at some point, contemplated ending his or her life. Few of us do it, but everyone can appreciate the impulse and occasionally entertain the thought. Given the magnitude of the life that was dropped in his lap, it would be pompous and naive to criticize Kurt Cobain for acting on it.

Kurt Cobain’s death was not an accident. It was a shame.

Steve Albini, a Chicago-based recording engineer, worked with Nirvana last year on its third and final studio album, “In Utero.”